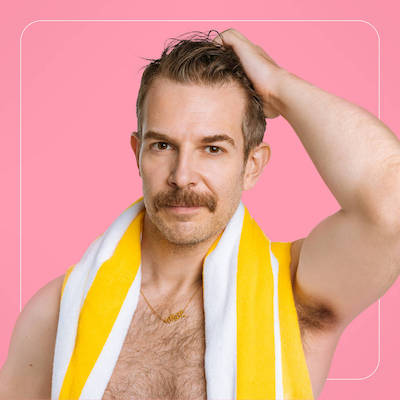

Matt Harris reviews the latest documentary on Hollywood icon Montgomery Clift.

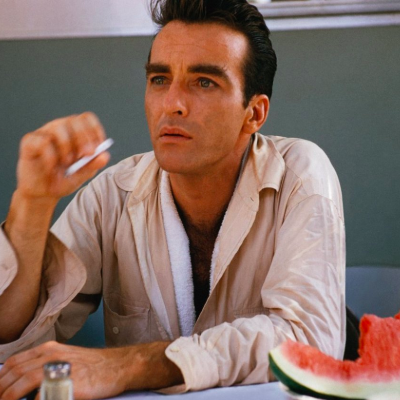

Montgomery Clift was one of the most beautiful and talented stars of the later Hollywood golden age, frequently held up alongside James Dean and Marlon Brando as one of the great Method Actors of the 1950s. Making Montgomery Clift is directed by the actor’s nephew Robert Clift, and Robert’s wife Hillary Demmon. Their research was helped not only by their proximity to the film’s subject but by the truly vast archive left behind by Monty’s brother Brooks (Robert’s father). Brooks filmed, taped, recorded and hoarded almost obsessively, leaving behind a treasure trove of material about Monty and the rest of the family. It’s this astonishing archive that provides the basic for a long-overdue reevaulation of Clift’s life and career.

Monty’s bisexuality and relatively young death from drug addiction has been the subject of much lurid speculation and prying over the decades – most notably, in two biographies from the 1970s by Robert LaGuardia and, later, Patricia Bosworth. Bosworth’s biography, in particular, remains the authoritative book on Clift and has shaped his public image over the last forty years. Making Montgomery Clift is not a conventional biographic story of the actor’s life, but rather a forensic examination of how his image has been shaped and distorted.

As a huge fan of Clift myself, I found this documentary a revelation – so much that we’ve taken for granted about him is exposed here as exaggerations or lies.

We also learn, significantly, that Clift was not tortured by his bisexuality, but embraced it and was comfortable in both himself and in his relationships with men and women. The tragic stereotype of a man driven to drugs and drink by self-hatred is a cliche that sells books but simply doesn’t reflect fairly on the reality of Clift’s life. It’s always nice to be reminded that queer history isn’t just endless repression and persecution.

Sometimes, it can be a problem when a documentary maker is too close to the subject, as it can end up somewhat hagiographic. Clift died of a heart attack at the age of only 45, after years of heavy drug abuse, though this film really implies that he just dropped dead of natural causes. There’s a danger, then, that in their keenness to rehabilitate Clift’s image the filmmakers may have actually sanitised him somewhat.

I suggested at the Q&A after the film’s screening at BFI Flare Festival that this might be the case, a suggestion Robert Clift rejected entirely. Demmon, however, responded with the very reasonable argument that that story – of Clift’s decline, his drug addiction and struggles – has already been told. Making Montgomery Clift is a documentary with a very specific agenda, but the film is open about that agenda and handles it well.

In spite of its obvious partiality, this is a great documentary, that sheds a whole new light on a very familiar subject. Anyone who is a fan of Clift – of Old Hollywood, acting or gay history – should see this.